Going back 200 years in

history we find that American women during the Antebellum Era were limited to only

certain career options. Only those to be considered genteel such as seamstresses,

shop keepers, laundresses, maids and cooks are among the few accepted feminine

occupations. Very few were even educated and those who were only knew the basic

of reading and writing skills. However, it was in the 19th century

that the idea of change in women’s roles were coming to a pique; the radical

feminist movement of the 19th century would help pave the way for new

ideas that would transform the new century. Although there have been great

changes in the roles of American women since the antebellum era, the education

and career opportunities now available to women are the greatest improvements.

In

19th century America at the beginning of the Antebellum Era, women

carried an important, yet invisible role in society. Women had duties very much

as strenuous as men. According to Howard Zinn, author of A People’s History of the United States, a common housewife of

these early years would have been expected to have “baked and brewed, pickled

and preserved, spun and sewed, made soap and dipped candles”, as well as be

able to treat family ailments, cook, raise children and most likely be responsible

for their preliminary education (Zinn). Although there already did exist

acceptable jobs outside the home for a woman, the ideal place for her was at

home, according to Coventry Patmore’s popular narrative poem of Angel

in the House. This poem from a 19th century man’s perspective, shows

what men think an ideal woman should be. Angel

in the House popularized and contextually influenced the development of the

idea of the cult of true womanhood as well. This concept of the ideal woman opposed the thought that

women had an equally capable mind as men. The cult also taught that too much study harmed the female mind. Therefore,

women were deemed incapable of leading or participating in political, and

financial matters as well as pursuing an education. Although a British

production, Angel in the House greatly

influenced the young and impressionable Americans as well. During the

antebellum era in the 19th century we still see women who although

strong, are being politically, economically and socially oppressed.

According to Antebellum Women by Carol Lasser and

Stacey Robertson, Education played a critical role (Lasser and Robertson 28).

Young ladies were encouraged to attend dame

schools, or finishing schools, known as refinement institutions where young

girls were taught basic skills in reading, writing and sums (Lasser and Robertson

29). However, the majority of their education in these educative institutions

was composed of female arts and other topics which flattered women such as the

arts in music and dance (Lasser and Robertson 29). One example of a dame school is Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield

Seminary mentioned in Antebellum Women (Lasser

and Robertson 31). However, it was very difficult for women to pursue a more

depth and professional education. In fact, prior to the civil war, only three

colleges were open to women according to History

of American Education by Harry G. Good (482). It is not even clear whether

any of the educators were women.

College level education

was hard to come by for Antebellum Era Women. Joel Perlmann and Robert A.

Margo, authors of Women’s Work? mention

that at the beginning, it wasn’t because communities denied girls higher

education, it was rather because “they were not sent by their families.” (25).

Of course, there were other ingrained factors as to which they were not sent.

Such ideologies that a higher education was a waste because ladies were meant

to marry, after which, they’d dedicate their lives to their households. There

was also the great doubt that women were capable and equal as men in mental

prowess. These stereotypes were influential factors that would affect the

importance of women’s education. Even by 1850 and 1860 the higher number of

student’s genders was always ranked higher by males than females whether in the

North or the South according to a chart by Perlmann and Margo (62).

Elizabeth Blackwell is an

example of a pioneer educator as she opened the first institution in the

medical field for women in the antebellum era. Blackwell was also recognized as

“America’s first woman physician” in her autobiography Pioneer Work Opening the Medical Profession to Women (Blackwell v).To

achieve her own education was a struggle, and in the end she was accepted

because of an accident (Blackwell viii). Emma Willard, another Antebellum

woman, was a female activist and prized education and the capacity of the

female mind. In her book, A Plan for

Improving Female Education, her goal was to “convince the public, that a

reform, with respect to female education, is necessary” (Willard 1). Emma

Willard is also a pioneer in America’s women history because she created the

first woman’s institution for higher education (Willard iii). In Lydia Maria Child Selected Letters,

1817-1880 by Milton Meltzer, Patricia G. Holland and Francine Krasno, Lydia

Maria Child was a feminist writer born in 1802 and was also a school teacher

when she was a teen (xi). At that current time, the number of female educators

were not prominent until “later, especially between 1830s 1860” according to Perlmann

and Margo’s Women’s Work? (22).

The challenges of

domesticating the newly obtained American territories in the Antebellum Era,

gave women the opportunity to fill the gap in which not enough men could fill.

In other words the ideal woman would

become a man’s greatest asset. One gap that women helped fill was by becoming

schoolhouse teachers. Important American women figures who influenced change

was First Lady Abigail Powers Fillmore. According to Kirsten Hoganson’s Abigail Powers Fillmore 1st lady

1850-1853, Abigail was like many young women educated by her mother at home

(Hoganson 99). Abigail constantly continued her studies through self-education

and went onto become a teacher to help financially (Hoganson 99). Cormac

O’Brien, author of Secret Lives of the

First Ladies gave details that Abigail’s star pupil whom she encouraged and

influenced to pursue his education was her future husband Millard

Fillmore-future President (72-73). Abigail P. Fillmore continued her career as

a teacher after marriage until the birth of her first child (Hoganson 100).

First Lady Fillmore was one of the few exceptions to which education and a

career was a priority.

There are several reasons

for which women became more prominent as educators. Perlmann and Margo explain

in Women’s Work? that by the 1840’s,

the prominent idea of female educators was appreciated as they were being

recognized for their nurture of children (Permann and Margo 7). There was also

the unfortunate fact that women were at this current time being oppressed

through their unfair wages. Women educators were cheaper to hire than Men

educators (Perlmann and Margo 7). By the 1850s many women, especially young

women were being hired to work as primary educators in the South while in New England,

84% of all rural teachers were women by 1860 (7). The need for educators was

being filled by those who were willing, like the women. As the Civil War grew

closer, more women were being educated and becoming educators as well, not only

in primary education or dame schools but in college level education as well.

After the Civil War, one

of America’s focus was in taming the Mid-West in America; therefore, opening more

doors to women education and educators due to the great need (Good 481). Among

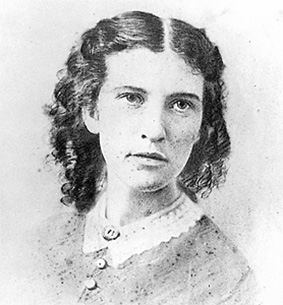

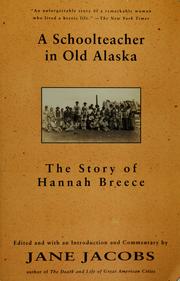

these real women educators who braved this wild land were Hannah Breece and

Miss Treva Adams Strait. Hannah Breece is described by her great niece Jane

Jacobs as one of the “Americans on the frontier” in her biography A Schoolteacher in Old Alaska (Jacobs

vii). In 1901, Alaska was still a very dangerous place, especially for women,

considering the un-dominated rough terrain, all the obsessive gold miners,

murderers, black-market traders and Natives there. Breece faced all these

dangers at the age of forty-five and taught “Aleuts, Kenais, Athabaskans,

Eskimos and people of mixed native and European blood in Alaska” for fourteen

years and in skirts and petticoats as well! (Jacobs vii). Later on in 1928,

many women opted for the more accessible option of teaching in the Mid-West

country like Trevia Adams. According to Adam’s autobiography Miss Adams, Country Teacher, she was 18

when she began teaching, eager to become financially independent (Strait 3).

This desire of becoming independent women would win over society, not only as

educators, but other careers as well.

Moving forward from the

Antebellum Era, we see a stark contrast with American women today. There is no

longer that barrier where a women in America is deterred from pursuing a

certain education or career because of her gender. Examples of intellectual and

successful women in their respective careers today includes Hilary Clinton, who

is involved in the nation’s politics and aspired to run for the presidential

seat according to Biography.com (Hillary

Clinton Biography). Clinton is a graduate of Yale Law School and was also First

Lady of the United States (Hillary Clinton Biography). She now continues her

occupation as a government official and a Women’s Rights Activist according to biography.com. Condoleezza Rice, “is the first black woman to

serve as the United States' national security adviser, as well as the first

black woman to serve as U.S. Secretary of State”, she continues today as a

government official (Condoleezza Rice Biography). I conclude with our current

President of San Diego City College, Lynn Ceresino Neault. According to San

Diego State University’s “Student Biographies” Lynn Neault studied with them

and achieved her B.A. and M.A. in Public Administrations. She has since been working

for the San Diego Community College District (“Student Biographies”). Women can

now proceed to fulfill any ambitious dream today.

Finally,

considering all the changes these prominent women began in their day for a

brighter future, educational and career opportunities for women are the

greatest improvements. I am very thankful for the opportunity to have learned

about these women. I can look back and see how far we have come. Because of

them, I am now free to make the choices I desire for myself and my future

career as a woman of the 21st Century in America.

Works Cited

Blackwell, Elizabeth, Dr. Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical

Profession to Women: autobiographical sketches. London: Longman, Green, and

Co., 1995. Print.

Cardamone-Fox, Lee. “Inequity in the academy: A case study of factors influencing

promotion and compensation in American universities.” Forum on Public Policy Online 2010.5 (2010): 1-17.ERIC. Web. 13

Mar. 2014.

Child, Lydia Maria. Lydia Maria Child, selected letters, 1817-1880. Amherst: University

of Massachusetts Press, 1982. Print.

Cokie, Roberts. Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised

Our Nation. New York: Perennial, 2005. Print.

"Condoleezza Rice." 2014. The Biography.com

website. Apr 22 2014

Good, Harry Gehman, and James David Teller. A history of American education. New

York: Masmillian, 1973. Print.

Harris, Sharon M. Women's

Early American Historical Narratives. New York: Penguin, 2003. Print.

"Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton." 2014. The

Biography.com website. Apr 23 2014.

Jacobs, Jane and Hannah Breece. A schoolteacher in old Alaska: the story of

Hannah Breece. New York. Random House. 1995. Print.

Lasser, Carol, and Stacey M. Stacey

M. Robertson. Antebellum Women: Private, Public, Partisan. Lanham: Rowman &

Littlefield, 2010. Print.

Perlmann, Joel. Women's

work? : American schoolteachers, 1650-1920. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 2001. Print.

Strait, Treva Adams. Miss Adams, country teacher: memories from a one-room school.

Lincoln: J & L Lee Co., 1991. Print.

“Student Biographies.” 2010. The Eddleaders.sdsu.edu

website. April 23 2014.

Willard, Emma. A

Plan for Improving Female Education. Middlebury: S.W. Copeland, 1819. Web.

2014-today. Play.google.com. Web.

March, 2014.

Zinn, Howard. "6. The Intimately Oppressed."

A People's History of the United States. 20th ed. New York: Harper

Perennial Modern Classics, 2003. 103+. A People's History of the United States.

Steven, 6 Sept. 2006ss. Web. 23 Apr. 2014.

_(3816540623).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment