Primary Analysis

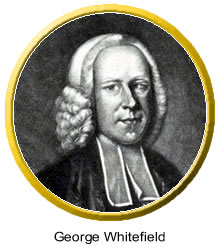

Benjamin Franklin wrote Upon Hearing George Whitefield Preaching

in 1771. This account was written in Franklin’s autobiography testifying to his

readers the historical event of witnessing Evangelist George Whitefield

preaching to an enormous crowd during the Great Awakening.

Two significant events that were

occurring at the time of this event were the Great Awakening and the rise of

power among women near the end of colonial America. First of all, a great evangelist who took

part in this religious phenomena of the Great Awakening was George Whitefield.

Whitefield preached powerful words that reached and filled the need and void of

many people (Oakes 122). The sermons given in revivals during the time of the

Great Awakening brought on religious fervor and unity among the people as

Benjamin Franklin said in the following:

The Multitude of all Sects and

Denominations that attended his Sermons [i.e. Evangelist George Whitefield]

were enormous…It was wonderful to see the Change soon made in the Manners of

our Inhabitants; from being thoughtless or indifferent about Religion, it

seem’d [seemed] as if all the World were growing Religious, so that one could

not walk thro’ [through] the Town in an Evening without Hearing Psalms sung in

different Families of every Street (63).

Whitefield’s

life and relationship with God was very well known that even soldiers used his

clothes as relics for protection five years after his death (Oakes 122).

During this time as well, women were gaining more respect and

wielding more power in the home due to the arduous work that they contributed

to the home. “Between the American Revolution and the Civil War, so many

elements of American society were changing-the growth of population…changes

were bound to take place in the situation of women” (Zinn). It was also out of practicality that frontier

women were gaining some degree of equality among men in the world and within

the home (Zinn). For example, Martha Moore Ballard, a typical American

housewife, “‘baked and brewed, pickled and preserved, spun and sewed, made soap

and dipped candles’” (Zinn). It is estimated that as a midwife for twenty-five

years, she would have delivered “more than a thousand babies” (Zinn). A woman’s

role in the home was also important due to the fact that education transpired

within the home itself (Zinn). However, more women were practicing more

freedoms outside of the home as well as they began working “at important jobs-publishing

newspapers, managing tanneries, keeping taverns, engaging in skilled work. In

certain professions, like midwifery, they had a monopoly” (Zinn). All these

causes for which women were beginning to step outside their regulated power,

obtaining more and not following the normal gender roles of society were the

stepping stones to even greater changes in the next century.

The purpose for which this document

was written was to relate Franklin’s encounter, reaction and observations of

the effect of that the words of Revivalist George Whitefield had on Colonial

America. Although it is not documented that Franklin shared a personal

encounter with God, he nonetheless, believed greatly in self-improvement. Consequently,

he could not understand how such great multitudes would listen avidly to a

speaker who would call them, “half Beasts and half Devils” (Voices 63).

Therefore, Franklin also marveled and felt excitement while observing the

influence Whitefield had over his audience and how they were stirred to positive

changes (including himself). Benjamin also wrote about his petty disagreement

with Whitefield about his plan to raise money to build orphanages in Georgia

instead of bringing the orphans to the New England colonies. Because Whitefield

would not heed to Franklin’s advice on this matter, he retracted his thought of

contributing financially to this cause. Benjamin Franklin comically confesses

at the end of this excerpt that upon hearing Whitefield’s words at the ending

of his sermon, he begins to soften and

become ashamed; during which he

gradually resulted in emptying his pockets of money for Whitefield’s charity. This

reading ties in nicely with Oakes because at the beginning of chapter five, it

begins directly with an American Portrait of George Whitefield: Evangelist for a Consumer Society. This directly

addresses to a similar occasion of which Franklin would have observed in his

own experience.

Many

historical scholars believe and state that this excerpt from Franklin’s autobiography

suggests the persuasive powers of George Whitefield are related to his great oratory skills, therefore, the

consequent reason for which Franklin admired Whitefield. However, just how many

of these historical scholars who believe, state and teach this idea—including

Franklin himself, have actually had such a similar personal encounter with God

like Whitefield, his listeners and other people who have thus experienced what

Franklin wrote about? Whitefield’s words were spoken with great power and held

the ability to persuade the hearts of the people, even the unwilling ones such

as Franklin. The reason behind this is because as Whitefield said, “I

endeavored to do all to the glory of God,” (Oakes 121) which he attempted to

complete to the best of his human ability. As a result, God’s glory was upon

Whitefield as well. The word’s he spoke were reinforced by the power of the

Holy Spirit. In view of that, many who understand the spiritual side of what occurred

in this event will not be as puzzled as Franklin towards the reaction of

Whitefield’s listeners.

This

reading was interesting because of Franklin´s foolish behavior in the beginning

and how one see´s the change in him towards the events he is witnessing and

experiencing. He seems almost childlike as he watches in awe as the multitude

accepts Whitefield’s use of name calling. I was disappointed in him when he

became petty over a disagreement with Whitefield. However, at the end of this

reading I laughed as he felt himself under the influence of the Holy Spirit,

which he felt himself powerlessly persuaded to give in. This same feeling

continues to occur even today. Like Franklin, I’ve found myself under this same

persuasive power as well and I see God’s use of humor as he uses his Holy

Spirit to compel me to act or refrain from certain things. When it clicks in my

mind of what is going on, I can only shake my head smilingly and say, “Ok God,

you win.”

_(3816540623).jpg)